Let’s talk about Serbian names

If you type ‘Serbian names’ in Google search engine, you’ll get a list of the most interesting hits to complete your search: old Serbian names, Orthodox (church) Serbian names, Serbian international names, saddest Serbian names, unusual Serbian names, girl names people think are Serbian but are actually Arabic.

Make no mistake – a foreigner is likely to mispronounce any name from these lists except the international ones.

Maybe it’s because of our intricate yet wildly liberating alphabet. Maybe it’s because other languages have impossibly complicated pronunciation rules (I’m looking at you, English). Whatever the case, Serbian names are not easy to pronounce. They reflect tradition, beauty, and love for all things around us.

History of names

Since ancient times, Serbs carried anthrophonymic types of names whose origins were motivated by desires and wishes. A typical Serbian name dating back from circa 1445 is Dabiživ – da bi (bio) živ, which roughly translates to ‘to live’. A very popular name for boys that dates back to the Middle Ages is Bogdan – bogom dan, or ‘given by god’.

The fact is that most, if not all, old Serbian names were kept alive by the church. The Orthodox Church was keen on tracking folk names that existed even before the adoption of Christianity. During the dark Middle Ages on the Balkan peninsula and throughout the Ottoman Turks’ rule ancient folk names were the basis of Serbian nomenclature. With external influences – Muslim Turks, their language, and names – trying to violate the purity of Serbian names, there was a small percentage of that loanwords could not enter.

According to Milica Grković, who studied the names in the Dečan charter (1330), 90% of all names in the Dečan charter were folk names. Those included complex names (Bratoljub – the one who loves his brother, Dabiživ), self-created names (Ban – a noble title, Vuk – wolf), derived names (Miloš, Milan), and the grammatical types of hypocoristics.

Most of the names back then – and often nowadays – were created from the basis of several words like bog–god, drag–dear, mir–peace, brat–brother, rad–work, voj–battle, hrana–food. Following this rule, people were named Bogoljub, Bogdan, Dragan, Dragomir, Miroslav, Bratislav, Radomir, Radovan, Vojislav, Hranislav.

Names were also created as a reflection of the animal world: Vuk–wolf, Srna–doe; birds – Vran–crow, Golub–pidgeon; plants – Jagoda–strawberry, Biljana–herbs; fire – Ognjen–flame, Vatroslav–fire; natural phenomenon – Zoran/Zora–dawn; metals – Gvozden–iron; descriptive adjectives – Leposava–pretty, negations – Nenad, Nebojša; also other things found in nature, inanimate objects, social positions, ethnonyms, abstract phenomena, colors, kinship, and from the anatomical lexicon.

Hardcore Serbian folk names started to prevail with the beginning of the Ottoman era – out of spite, no doubt – somewhere in the early 14th century. Most popular names were Bogdan, Vukašin, Vukan, Miloš, which are the typical Serbian names for boys even today.

Georges, Vladimirs, and Jacquelines

Many Serbian names come from other languages and countries. A lot come from Russia and the rest of the Slavic community across Europe, but also Greece. Greek Georgios has found its home in our language as Đorđe. It is a traditional variation among the Slavs and other Orthodox Christians, yet other nationalities have their own. Jorge is a popular name in the Spanish and Portuguese speaking world, but Italians too have their Giorgio.

Russian-inspired names are basically all of the old, ancient Slavic names shared across the Slav tribes before Christianity. It wasn’t unusual to name your child after rain, sky, ground, spring, or some badass Slavic god. Slavic names typically end in –mir: Vlastimir, Dragomir, Radimir, and –slav: Borislav, Dobrislav, Vladislav. Solid, traditional names rich in cultural background and paganism, but shunned from today’s maternity wards.

In more recent years, influences have come from all over the world. Many names were popularized by real historical figures, but also literature and movies. The 20th century saw the rise of celebrity-inspired names; Silvana Mangano, Jacqueline Kennedy, Valentina Tereshkova, Svetlana Alliluyeva (Joseph Stalin’s daughter), to name only a few.

In some parts of Serbia, mostly rural ones, you can meet anyone from Silvana to Tarzan. The undying love of the world’s famous martial artist has rendered few boys Brusli (the phonemic transcription of Bruce Lee). I went to kindergarten with a boy whom parents consciously named Majkl in tandem with the last name Džontić. He’s literally Michael Johntić.

What about last names?

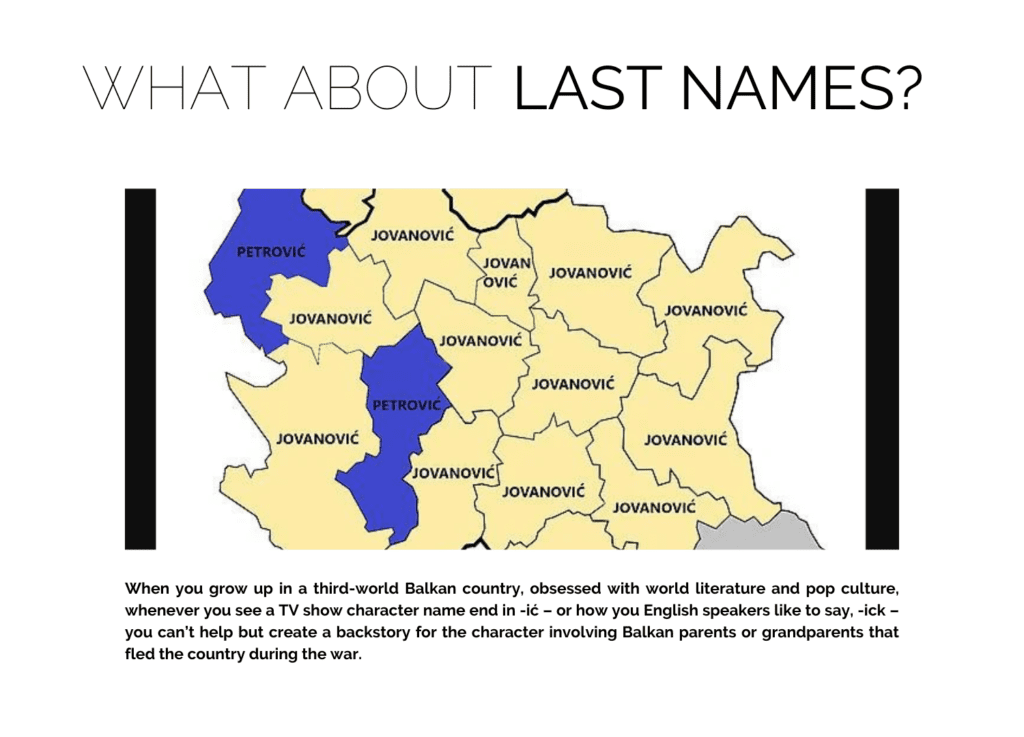

This might be the most Serbian thing ever, the hallmark of Serbian recognizability across the globe. Novak rocks it proudly, a couple of other rockstar athletes, as well, and we have one Nobel prize winner that cemented it as the ultimately Serbian thing – an estimate of two-thirds of all Serbian last names end in -ić, sometimes -ović.

This suffix is a Slavic diminutive that used to function to create patronyms – Petrović means little son of Petar. Croatian, Bosnian, and Montenegrin surnames share this trend, as well – although you’ll recognize a Bosnian last names much easier since they tend to end in -begović (from beg/bey, an Ottoman noble title).

When you grow up in a third-world Balkan country, obsessed with world literature and pop culture, whenever you see a TV show character name end in -ić – or how you English speakers like to say, -ick – you can’t help but create a backstory for the character involving Balkan parents or grandparents that fled the country during the war.

In the early 19th century, a new trend of last name-giving rose. Namely, among the Serbs that lived across the rivers Danube, Drina, and Sava – think present-day Hungary, Croatia, and Bosnia – many surnames were invented based on professions, toponyms, traits, even nicknames. Since back then those parts belonged to the Austro-Hungarian empire, Serbs tried to keep their cultural identity by adding -ić to the end.

However, the 19th century Austro-Hungarian administration would typically change anything -ić to -ov, -ev, or -ski, among others, as to make those names and, by extension, the name owners less Serbian. Some say their goal was to culturally separate Vojvodina Serbs, present-day Vojvodina region in the north of Serbia, from their brethren in the south.

You can make any name Serbian. Danielle Santarelli, an Italian volleyball coach and the head coach of Serbia’s women’s national team, has already been Serbified. We now call him Santarelić because it’s cool and affectionate – he did just win us a gold medal at the World Championship. This fun game allows us to Serbify others, as well – Robert Denirović, William Faulkerić, Michael Jordanović.

Now you try.

Modern parents want their children to be unique, so they choose the craziest names for their babies. Shout Mia, or Lea at a children’s playground and see how many girls and dogs turn their heads.

Despite the meddling of our Slavic roots in our naming practices, a lot of names are not Slavic but still reflect our Christian faith. Some names in our language originated from Hebrew, carrying Biblical reasons and tradition. We have made those names feel welcomed and made them sound typically Serbian – John the Baptist became Jovan (yoh-vahn), Mary became Marija (mah-ree-yah), angels Michael and Gabriel are Mihajlo (mee-high-loh) and Gavrilo (gah-vree-loh), while Christ’s apostles Matthew and Paul took on their Serbian variations of Matej (mah-tey) and Pavle (pahv-leh).

Serbian names are often traditionally apotropaic – protective of their owners. The most famous case of apotropaic names is the one of Vuk Karadžić, our famous philologist and reformer of the modern Serbian language. His name means ‘wolf’, as he once wrote: “When a woman has troubles conceiving a child, and names her firstborn Vuk, she thinks that the fierce name will protect her son from child-eating witches.”

Some of our names are 100% fuss-free to utter. Think Ana, Marina, Stefan, Marko, Katarina. Others exist purely as a means of ridicule of their owners. Can you say Dragoljub? What about Milica? Ognjen? If I had a dollar every time someone called me vahn-dza instead of vahn-yah, I’d be filthy rich. Don’t worry, it’s not your fault. It’s your overly complicated phonetic, phonemic, and other words starting with phon- structures.

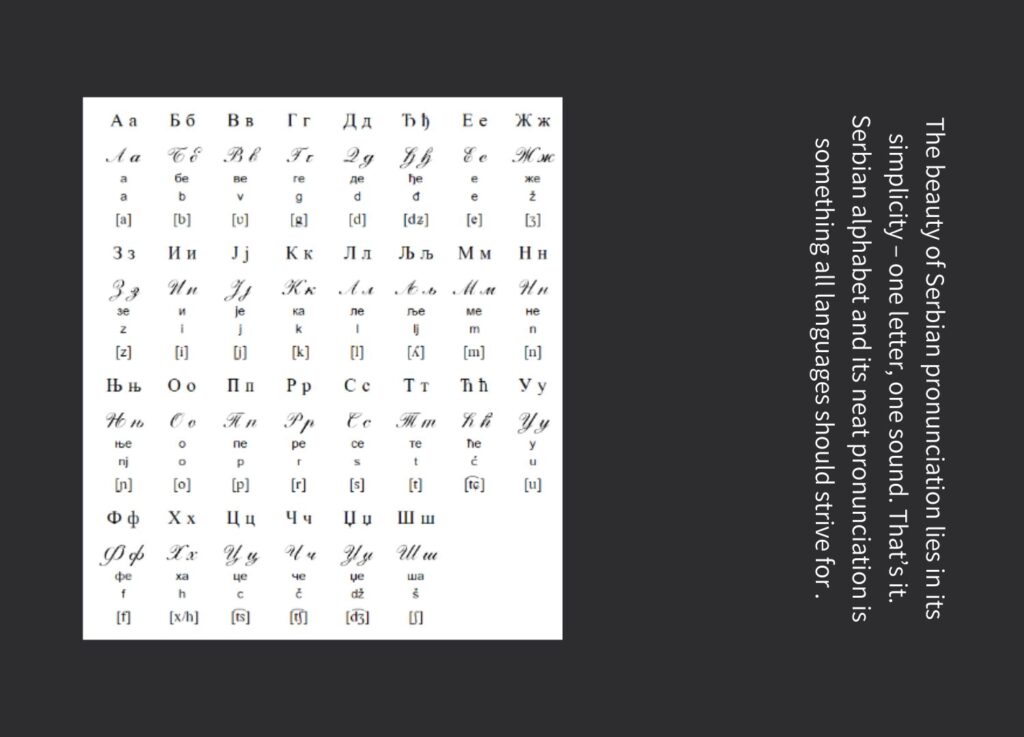

The beauty of Serbian pronunciation lies in its simplicity – one letter, one sound. That’s it. Serbian alphabet and its neat pronunciation is something all languages should strive for (I’m still looking at you, English).

George Bernard Shaw, the great Irish playwright, believed that the Serbian phonetic alphabet was the most perfect script in the world. In his will, he left a considerable sum of money to an Englishman who would successfully reform and simplify the English alphabet based on Vuk Karadžić’s model.

Clever man, that George Bernard Shawić.

Truly Yours,

Vanja