Why Do We Tell Stories?

It’s in our human nature to wonder. We wonder about others and the world around us, and we wonder about ourselves. Today we wonder why we write.

My man doesn’t read books. A waste of time, he says. The last time he held a book in his hands (and actually read it) was probably in middle school if that. He was a basketball player and advanced in his academics mainly through shooting hoops and playing in Serbia’s minor leagues. But his basketball career has ended and he still doesn’t read books. If it weren’t for our three-year-old, he wouldn’t even read bedtime stories. (Do five-page twenty-ish-sentence books count as light reading?)

But I often snatch an hour or so before bed to catch up on my library material. During that time, my man is flipping through the sports channels, watching reruns of NBA or big European basketball league games, gobbling on the highlights and statistics as if his life depends on it. And then he asks me—why are you wasting time reading?

I could ask him the same question—why are you wasting time watching that game?—but I don’t. (Okay, I sometimes do, but for the sake of the point I’m trying to make, let’s say I don’t.) I know he loves it, he thoroughly enjoys watching big b-ball stars compete against one another, breaking records, and writing history. Is it a waste of time? Maybe. Could he be doing something more productive instead? Definitely. Is watching sports his passion? Absolutely.

We all have things we inexplicably love. That’s the whole point of loving, not being able to explain why you feel that way. You can’t give reason to love and passion no matter how hard you try. So why do we wonder, then, why do we tell stories?

The Library of the Family Gradinovački

My starting point is always a feeling of partisanship, a sense of injustice. When I sit down to write a book, I do not say to myself, ‘I am going to produce a work of art’. I write it because there is some lie that I want to expose, some fact to which I want to draw attention, and my initial concern is to get a hearing. But I could not do the work of writing a book, or even a long magazine article if it were not also an aesthetic experience.

–George Orwell

Perhaps the story about a Serbian family could help find an answer to this question. The 2020 novel written by Snežana M. Veljković revolves around a wealthy family from Sombor at the turn of the 20th century and their love for books. The main character, Andra Gradinovački, has inherited the family passion and obsession of collecting scrolls, manuscripts, and forbidden books that document the painful Second World War events, but also pre- and post-war ways of life.

The library grows with each generation, enriched by its members, family ties, and world events. By the time the story reaches modern times, the library becomes a treasury, an homage to every single piece of writing contained in it, and a remedy for oblivion.

A good portion of the plot is dedicated to the brave characters who face the 1941 bombing of Belgrade and the Nazi occupation. People were being shot in the street, hung in public squares, and entire families ripped apart, and sent to concentration camps. Among all that mayhem, Andra Gradinovački chooses to teach classes on Ovid’s Metamorphoses. His wife asks him: “Andra! Who cares about all that now?” But Andra responds: “You’ll be surprised to see how much people care about it.”

You’d think there are more pressing matters to care about in wartime, but Andra’s classes and his family’s library are proof that even in dark times when nations face extinction, there is something that will outlive us all.

The Eternal Art of Storytelling

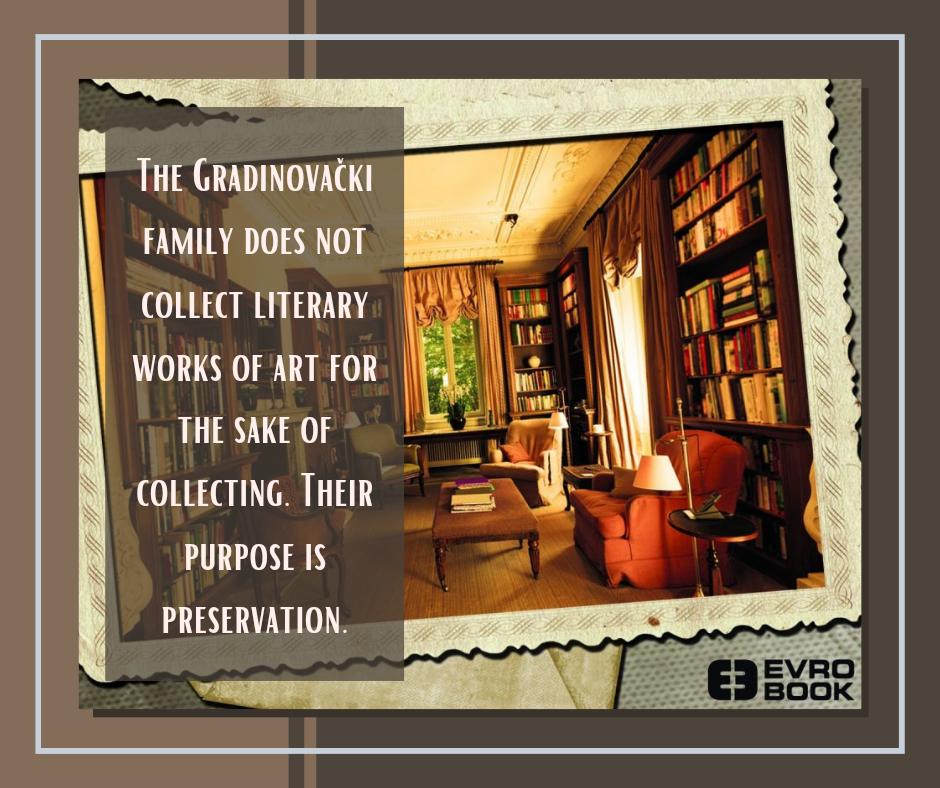

The Gradinovački family does not collect literary works of art for the sake of collecting. Their purpose is preservation. When Andra meets his future wife, the beautiful Zika with a mysterious name, he is instantly reminded of Ovid. The way he depicts the metamorphoses of human nature and wonders whether they have come out of the same strengths and weaknesses, motivations, and urges that we share with gods. Andra was fascinated by the Roman poet’s insight into human nature; love, lust, kindness and evil, wisdom and stupidity, all that makes us human.

Metamorphoses are more than two thousand years old. It was relevant then, and it sure is relevant today. Without Ovid, there wouldn’t be a Dante, or a Chaucer, not even a Shakespeare to torment English students everywhere. Without Shakespeare, there wouldn’t be Shaw or Orwell, or the great Ivo Andrić, for that matter.

I know it doesn’t make much difference for someone like my husband, but for me and others like me—bashed on the head with volumes of Shakespeare and the Canterbury Tales at universities—the world without them would be a terrifyingly empty place.

The most important feature of storytelling is having someone to tell your stories to. We don’t keep stories to ourselves. It’s the innate human drive to share experiences with others and connect. Sometimes the effect of the story is more important than its content; more important than truth. That’s why we embellish, exaggerate, invent, and turn facts upside down to fit our narrative. What’s the most wonderful thing about stories? We always, always find new ways to tell them.

Why Do We Really Tell Stories?

I am not able and do not want, completely to abandon the worldview that I acquired in childhood. So long as I remain alive and well I shall continue to feel strongly about prose style, to love the surface of the earth, and to take pleasure in solid objects and scraps of useless information. It is no use trying to suppress that side of myself. [But] all writers are vain, selfish, and lazy, and at the very bottom of their motives there lies a mystery.

–George Orwell

There’s no logical explanation for why we write and create, tell stories, and invent worlds. We just do. The world we live in, as fragile and flawed as it is, encourages us to pursue depictions of things and people we know and fantasize about more ideal worlds.

We write stories because we can. Sometimes because we must. Sometimes we are invited to tell stories and give a voice to things trapped in triviality. Serbian author Ana Atanasijević admits she was invited to tell the story of Nikola Tesla’s friend and admirer and shed light on the position of women in the 20th century. We all carry stories inside us. Thanks to the evolution of our brains and opposable thumbs, we are now fully capable of thinking of the unthinkable and writing what’s never been written before.

We write because we’re curious. Because we often need to escape our too-realistic, boring lives and explore the lives of others. We write because we want to change something about our world or point out that something should be changed. We write because sometimes we need to tell the truth. Other times, we try to conceal it within stories of imaginary creatures and superheroes.

After all, we are what we continually do (or think, or eat). If you read, the chances are you’ll want to write one day. And if you read a lot, you’ll probably have a story in you brewing for a while before you finally muster the courage to jot it down. Braver people before us have paved the way, for whatever reason they chose to be writers. Stephen King says he doesn’t write for money or to get famous. He writes for the joy of it. If you can write for the joy of it, you can do it forever.

Books are not a necessity from a purely existential perspective. If a zombie or brain-eating fungi apocalypse hits tomorrow, no one will be scavenging for books in the lack of water, food, and shelter. Books, literature, libraries—we need those to feed our minds and souls and to lock in everything that’s beautiful and meaningful in life. We write to communicate with those who came before us and with those who will come after.

Could Ovid have known that, in the next few millennia, his verses would inspire endless generations of poets and storytellers?

To escape your mundane modern lives, I recommend Snežana M. Veljković’s novel, The Library of the Gradinovački Family, to remind you of simpler times and raise questions about family, love, and the unchangeable nature of humans.

Truly yours,

Vanja