“Here lies the reader that will never open this book.

Here, he forever dies.”

-Milorad Pavić

It’s 1984. John Clancy has just published The Hunt for Red October, while Stephen King treated his readers with The Talisman. As Kundera explores The Unbearable Lightness of Being, something magical happens on the Balkan peninsula.

A man walks into his publisher’s office in Belgrade and delivers his freshly typed manuscript. It says Dictionary of the Khazars: A Lexicon Novel in 100.000 Words on the first page. I’m sorry, the publisher says, we’re not looking into publishing a dictionary. Milorad Pavić smirks. But it isn’t a dictionary!

The publisher raises his or her eyebrows (it is 1984, the odds are it was his eyebrows), and asks: So, what is it about? Well, Pavić says, already expecting this most detested question among authors, it’s a novel about the Khazars written in the form of a dictionary. The puzzled he-publisher is now tempted to show this unusual man with the most unusual book out the door.

Luckily for the rest of us, he didn’t.

Dictionary of the Khazars celebrated its 38th birthday this year and is still one of the most intriguing pieces of the written word.

“The writer advises the reader not to attempt reading this book without great trouble. And even if he does, let it be on those days when he feels that his intelligence and caution reach deeper than usual, and let him read it like a ‘firefly’ or a ‘leaping’ fire, a disease that acts up every other day and affects the patient only on women’s days of the week…”

It’s all about the readers

Dictionary of the Khazars was the first novel Milorad Pavić ever wrote. To conceive such a delicately complex plot told in a unique way is what genius is made from. The book addresses the mass religious conversions of the Khazar people, an actual historical people whose fate was given a Tolkienesque fantasy trope.

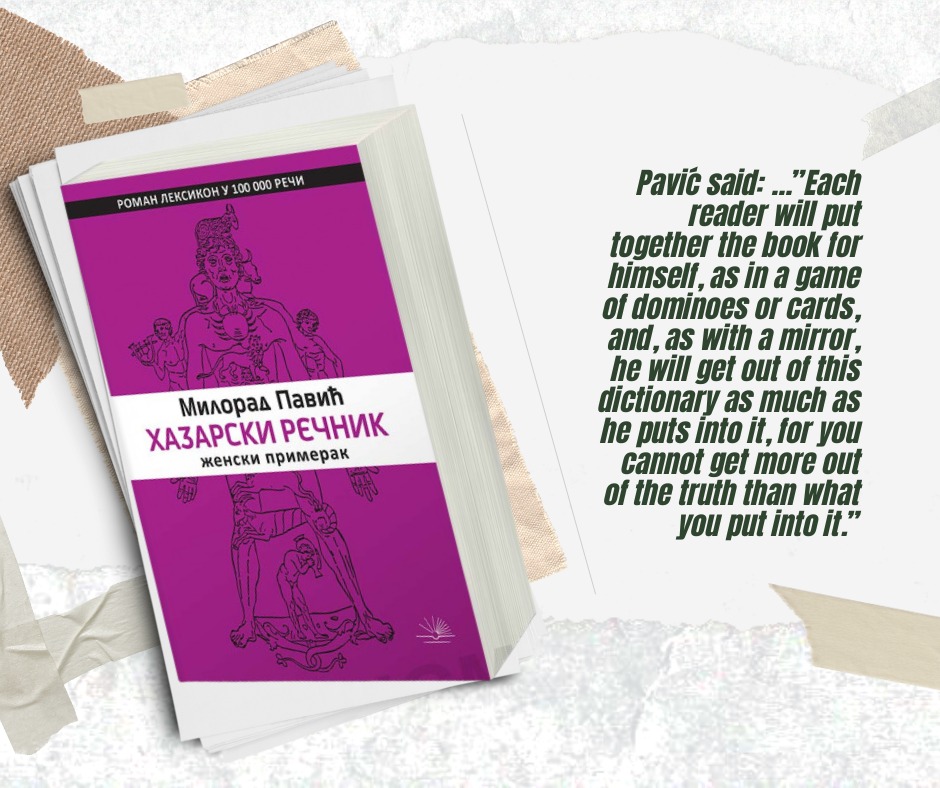

Pavić said: …”Each reader will put together the book for himself, as in a game of dominoes or cards, and, as with a mirror, he will get out of this dictionary as much as he puts into it, for you cannot get more out of the truth than what you put into it.”

In the author’s words, the story about the Khazars was a metaphor for a small people surviving between great powers and religions. Even 39 years after publication, this book is more relevant now than ever. As one French critic said: “We are all Khazars in the age of nuclear threats and poisoned environments.”

Although the plot relies on the narration about the Khazars, they are not the heroes of the book. The real hero – or the villain – is the reader. The reader chooses how much, or how little, they will read. All the reading parameters have been left to the readers. Pavić wrote the words, it is up to us to give them meaning.

When it first appeared in 1984, it had female and male editions. In his foreword to the 21st century androgynous edition, Pavić explained that the man experiences the world outside himself, in the universe; the woman carried the universe within her.

Why the Khazars?

Khazar people once occupied the land of southeast Russia, southern Ukraine, Crimea, and Kazakhstan. The complete story about the Khazars seems to have been lost centuries ago, as little was known about their culture, language, religion, and history at the time the novel was conceived.

The book follows a semi-reliable multitude of sources that tell stories about the Khazars. It’s hard to tell whether we could trust them or not because they seem to contradict each other with completely different data. Each and every account of the lives and disappearance of the Khazar people could be plausible and, at the same time, entirely made up. Pavić drew inspiration from this tangled mess of narration to write layers about mysterious people who mysteriously disappeared. It is the reader’s task to untangle the enigma surrounding the Khazars from various points of view that tell a similarly different story.

The book is divided into three major parts, each one trying to reconstruct what happened to the Khazar people. The three mini-dictionaries inside this remarkable lexicon-novel contain sources of the ‘Khazar question’ (the mystery of their disappearance) answered through the eyes of three big religions. The Red Book tells of Christian sources, the Green Book of Islamic, and the Yellow Book contains Jewish sources of what could have possibly happened to them.

Another layer is given to the story, the one that deals with three timelines in which the narration about the Khazars take place – Middle Ages, 17th century, and modern 20th century. Three parts, three religions, three timelines… I know what you’re thinking, Serbian people are obsessed with the number three. (And you’re most likely right.)

As the story opens, we learn of a great Khazar qaghan (ruler) and his undecipherable dream. He employs three philosophers each one from different religious background – a priest, a rabbi, and an imam walk into a bar – to tell him what his dream means. Whoever offers the most acceptable interpretation of the dream, the qaghan and the entire nation of the Khazars will convert to his religion.

The ‘Khazar polemics’, or the Khazar question, as the dream interpretation is often referred to, was subsequently resolved, except we never learn how. The entire Khazar population, allegedly, has been converted to either Christianity, Islam, or Judaism, and every trace of the people was lost.

The very first entry in the Red Book is about the Khazar princess Ateh. Every night before bed, blind maids would paint her eyelids with letters from the forbidden alphabet of the Khazars. One look at those letters meant certain death. Thus, princess Ateh was unable to die, as she was protected by the forbidden letters all her life; not even Death itself would come near her.

If you think this is insane, try reading Dictionary of the Khazars for the first time as a fifteen-year-old girl with head bursting with imagination.

“For those buried in Čelarevo, the Hungarians would want them to be Hungarians or Avars, Jews to be Jews, Muslims to be Mongols, and no one wants them to be the Khazars. And they most certainly are… The cemetery is full of broken pottery vessels with engraved menorahs. As a broken pottery vessel marks a fallen, lost man with the Jews, so is this cemetery a cemetery of fallen and lost people, as the Khazars were in that place and perhaps in that time.”

A novel or a dictionary?

Pavić was a visionary. He wanted to change the way people read, to create a fresh new dimension to reading. His vision was to include the readers in the process of the creation of a literary work by giving them the freedom and the absolute power to choose how they will read it.

You can read Dictionary of the Khazars in more ways you could count. You can start from the beginning and work your way toward the end, just like you normally would. You could flip through the pages and find entries you feel like reading about. You could read it by colors and religions. The best thing? It never ends the same.

The novel was translated in more than forty languages since publishing. In all of them, depending on the alphabet of the target language, the novel ends differently. The original Dictionary of the Khazars was written in Cyrillic and it ends with a Latin quote: Sed venit ut illa impleam et confirmem, Mattheus.

But whoever wants to change the way we read must also change the way the novel is written. He must use completely new technique of writing the story, a technique that needs to predict different reading flows in advance!

Pavić abandoned the linearity of written language in favor of imagination and dreams. He renounced the traditional way of story-telling in order to become a mage of interactive fiction. It makes sense to pursue a non-linear concept of writing. Our lives may unfold linearly – we go from one place to another chronologically – but our dreams and our thoughts are anything but linear.

That’s why the concept of the lexicon is important. It allows the reader to travel around the book, take shortcuts or enjoy the more linear pathways. The title announced that there’ll be 100.000 entries in the novel, but that is just another misleadingly fun quirkiness of this book. The number doesn’t refer to the number of entries, but it is rather an important feature in order to call something a dictionary.

But don’t let others describe to you what Dictionary of the Khazars really is. The more they try to explain, the less sense it makes. You can get your own copy of the book (female edition) right here at Yu Bibilioteka.

Truly yours,

Vanja