The novel is dedicated to the lust for life, although it talks about illness – an interview with Marija Ratković

Marija Ratković is a woman who cannot be described in a sentence. She is a writer, theoretician, culture worker, journalist, and founder of the Center for Biopolitical Education, with BA from the Faculty of Architecture and PhD from the Department of Art and Media Theory at the University of Arts in Belgrade. Feminist and public health activist. Winner of several awards for activism and fight for human rights. Perhaps she is deliberately trying to remain elusive and resist definitions, but she approaches everything she does thoroughly and wholeheartedly.

In a similar way, her first novel, “Under the Shirt” (Contrast publishing) can be described similarly – it is elusive in the number of topics it raises, many of which are taboo. Nevertheless, Maria talks about them bravely and without restrictions.

The editor Dunja, a character from the novel, at one point tells the main character that she wants her to write “colors, feelings, blood and dick”, and that it is important to tell “the story about us” that is not told “by old farts, desperate housewives and privileged children who know nothing”. Can the novel “Under the Shirt” be reduced to these four key words? And who are these “us” that Dunja wants the main character to write about?

Like many women, Dunja does not recognize herself in the existing categories and raises her voice about it, wanting to rebel against the representation of women in literature, in the name of modernity, in the name of women with whom she shares experience and perhaps in the name of literature itself. The whole novel is, in a way, a fight against stereotypical or perhaps too artificial representations that are far from the real experience of women. Dunja did not accidentally say “colors, feelings, blood and dick” perhaps wanting to emphasize the complexity she would like to strive for – these words are not mutually exclusive and can exist simultaneously, but as we can see, not without conflict. Those complex women are interesting to me as an author, and maybe they come from stereotypes such as the sick woman, the best friend, the sitter, the rival, but they also go beyond them. More precisely, the conflict between empathy and violence, nuances of sex and feelings – most often even in the same character – is the most interesting scenic conflict for me.

The theme of sex from a woman’s perspective is one of the central in this book. In one interview, you stated that you spent three and a half years researching what it is that excites humans from this region in sex, and that the findings are terrifying. You also mentioned power relations. Is this exactly the counterweight to what the main character gives in response to the question “what is ideal sex for you?”, and she answers, “a safe one”? Can you clarify that answer?

I will say briefly, one of the most common sexual fantasies in this region is non-consensual sex, i.e. – rape, and that scares me. Then there are fantasies about fertility, making children – even if we are talking about gay sex or sex with trans people, and fantasies about incest, which is all understandable for a patriarchal society full of possessiveness with the pronounced importance of family and family relationships. As a contrast in relation to this “normality”, the sexual fantasy of the main character about sex as a space of safety arises because in a world where rape is a fantasy, violence and demonstrations of power are frequent and always present, it is understandable that a woman fantasizes about a world in which she will indulge and not be hurt. She also says that subjugation is the greatest subversion – the idea of complete surrender, a kind of giving up the competition for power.

The main character carries a lot of things under her shirt – needs, desires, pain – but also a scar that points to a radical hysterectomy, i.e. to what is not there. From your perspective, can we even talk about what is more important – what is present or what is absent? Or are the two inextricably linked?

Certainly, what is absent is more powerful, it shapes our life precisely by its absence, determining aspirations, lacks. Of course, it is an unbreakable connection, but we always have to learn to focus on what is, on what is present and, as Foucault said, to learn to see what is close and precisely because it is close and usual, we no longer perceive it. Sometimes we need to de-normalize our pain, because when it is constantly present, we get used to it. Pain, illness, and absence can help us reconnect with life. In the hours when the main character is in the hospital, when life is immediately threatened, all destructive impulses have disappeared. I have the impression that she often has the motive of inflicting pain on herself or others to feel life more fully. Although it is about illness, the novel is dedicated to the desire for life. The novel is dedicated to the lust for life, although it talks about illness

I assume that this is one of the most common questions of the media, especially since the main character is also called Marija Ratković, and I know that you have already said that it is up to the audience to find out to the end how autobiographical the novel really is. Can you share with us a moment, a detail, no matter how small, from the book that is autobiographical and tell us why it was important for you to write it down?

I appropriate the novel in its most important themes such as the lust for life – that is definitely a motive that is mine, then the discussion about compassion – whether it is learned, or we are born with it is a topic that privately occupies me. And maybe in the details – let’s say the episode when the main character eats kačamak, waits in the waiting room, when she goes to the cemetery, the music she listens to, then the landscapes of Belgrade or Susak, I lent her that. But there is no way that I would ever jump into the Ambis, I have a terrible fear of heights and anyone who knows me knows this is a real made-up story. Once I was really kissed by an unknown man on the street, it was beautiful to me, so I included it in the novel – but those are episodes. The real me is just a minor character in this story.

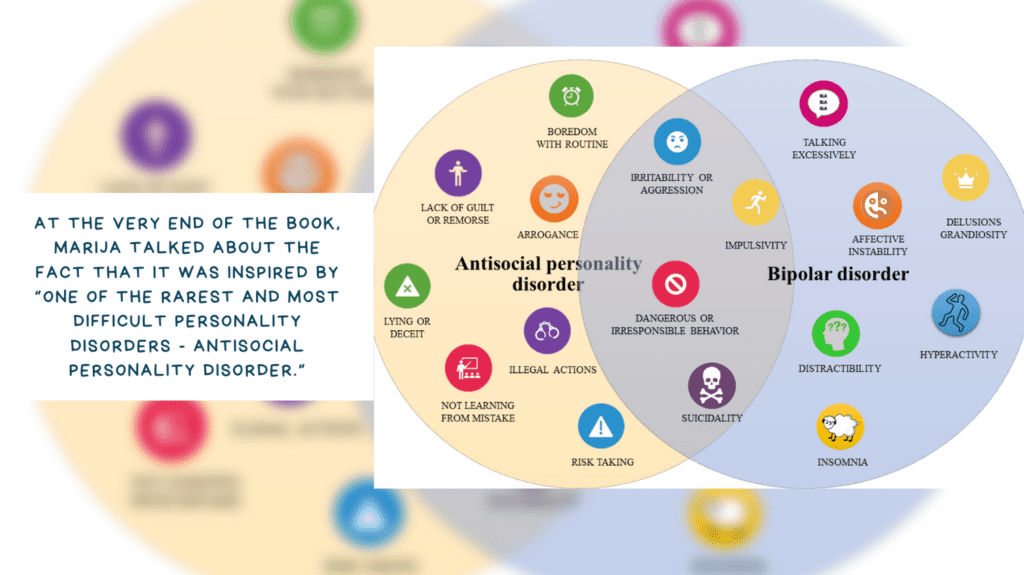

At the very end of the book, you talk about the fact that it was inspired by “one of the rarest and most difficult personality disorders – antisocial personality disorder.” Where did that inspiration come from? And additionally, as someone who works on the topic of public health, can you share some insights regarding the state of mental health in Serbia and is it still a taboo topic in our society?

The art world is fascinated by antisocial personality disorder and that’s something that bothered me. I had the need to enter the dialogue with countless fictionalizations of this rare and severe disorder precisely because there is also a large gender asymmetry – psychopaths are almost always men. Of course, this does not mean that men are bad – but that they are freer to break the law and norms. In fiction, it is very difficult to invent a Patrick Bateman who is female, because women are socially seen as compassionate. It was a huge challenge to build a character and take away her sympathy when it appears. Great avengers like Beatrice Kido (Kill Bill), Villanelle (Killing Eve) and Promising Young Woman – are not psychopaths, they always respond to what society has done to them. There is even a small essay tribute to Šefka Hodžić, the first woman who was sentenced to death in Yugoslavia – it is no coincidence that she is a barren woman and I see her awful crime as an amoral attempt to get out of the humiliated position into which society has pushed her. And I will answer exactly on that line – in a society of injustice, dark personality traits are continuously triggered and all potentials for mental disorders are realized. Society is a very important factor in mental health, and it is not possible to treat people without treating the society.

The novel begins and ends with the story of a relationship between two women who have been hurt by the same man, which begins with mutual stalking and ends with some form of understanding and even empathy. At the same time, your text at the end of the novel ends with a message about the importance of empathy and learning empathy. What conditions empathy, or the absence of it, when it comes to the relationship between women? What does it take to learn it and why is it important?

‘Under the Shirt’ brings the notion that empathy is learned, that it is meaningful and empowering, that it brings us much more than we lose. I had the impression that compassion is treated as a weakness in society, but I think it is necessary to think about it. Empathy is important in principle, but it is difficult for people to convince themselves that it brings them anything. And empathy can also be an exercise in strength – to bear life among people, to consciously sympathize instead of constantly fighting or stepping over others. Women are specific because of their subordinate role in society, they are forced into constant competition, proving and rivalry while at the same time being measured by how caring and tender they are. That’s why heroines who, even though they are women, have no basis in empathy, or even brag about their lack of compassion and therefore feel superior, together with their breakdowns, were important to me. When those old systems are broken and new ones are established, it’s as if life is renewed. What was important to me was conscious empathy, not the one imposed by society, just because we are women. Moments of true empathy are profoundly transformative.

The novel “Under the Shirt” is now available through the YuBiblioteka portal to people who have moved from our region to the USA and who follow the local literary scene. Is there anything you would like to say to them before or after they read this book?

The Internet has made it possible for us to communicate with the most distant parts of the world, and I am very happy that authorship has connected me with people I might never have met. I would tell the readers to write to their favorite authors and talk with them or among themselves about literature. For me, reading and writing in the 21st century has brought me new friendships, and it is certainly an opportunity that should not be missed.

S.P.