There is no place for cowards in literature – an interview with poet Radmila Petrović

Radmila Petrović is a young poet from Stupčević, a small town in the western part of Serbia. In the media, she is most often described as an “authentic voice of our contemporary literature” who writes about “the interweaving and conflict of traditional and modern, village and city, patriarchal principles and women’s issues”.

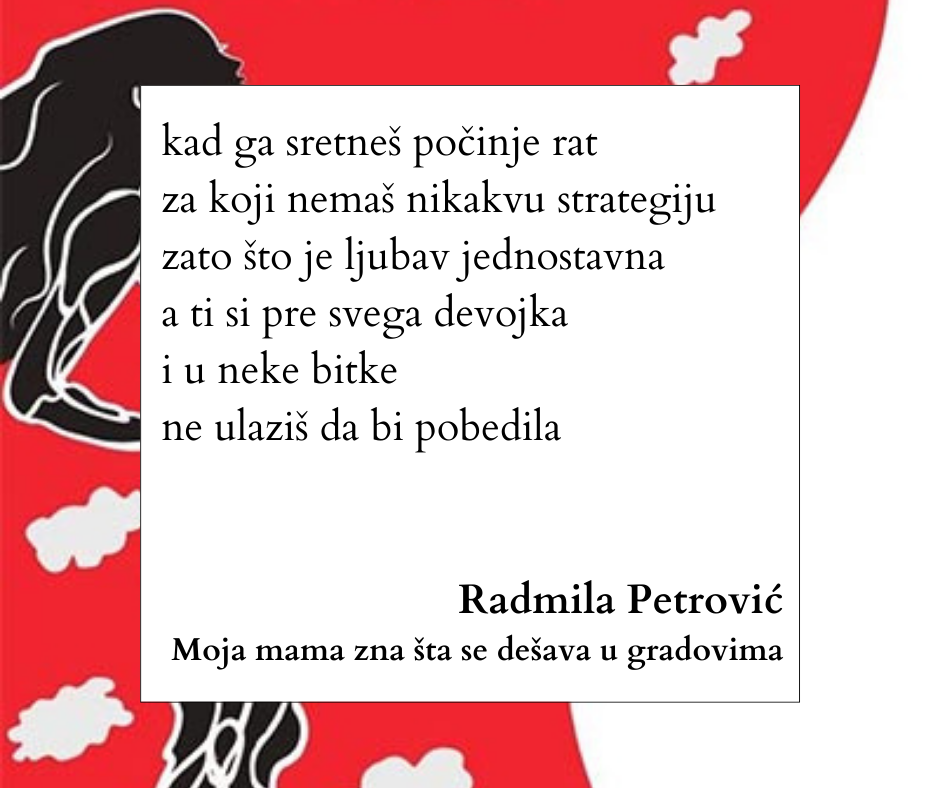

Radmila graduated from the Faculty of Economics in Belgrade, and she started writing poetry at the age of 16. Even before the collection of poems “My mom knows what is happening in the cities”, her poems were published, but this collection made her famous from Vranje to Subotica, and wider. The edition that this journalist has in her hands is already the fourth, because the previous book she bought ended up as a gift to a friend – which we learn from this interview is often the case with this collection and that for Radmila this is the biggest compliment.

Let’s start with the obvious question – how did the title of your collection of poems “My mom knows what happens in the cities” come about? What is happening in the cities and how does mom react to it?

I wanted the title of the collection to have an emotional value, both for me and for those who read it, but only after they read it. When its context is understood, it becomes ironic in a sad way. At first, it was difficult for me to pronounce it, not because of its length, but because of the significance it had for me intimately. Now it’s automatic, I’ve heard my name used next to that phrase so many times that I stopped noticing the meaning.

The title refers to all those warnings we receive from close people who often know little about the things they are warning us about. This is logical, as ignorance breeds fear.

Different things happen to different people, and moms being moms – they succeed or fail to understand what and why is happening to their children.

Topics that your poems address are still somewhat taboo in our society, and it seems that any narrative that opposes the dominant patriarchal one is being punished. What was your experience after publishing this collection of poems? Which reviews, whether they were positive or negative, left the strongest impression on you? How did your intermediate circle react?

I believe that in literature there is no place for cowards. The role of literature is to break the boundaries of the expected and conventional, to oppose each time with greater force. Relentlessness, in my opinion, should be the essence of art and those who create it. If you want to call yourself an artist, some price must be paid.

Everything that opposes the patriarchy is somehow punished in real life, but in literature, it doesn’t have to happen like that. Thus, most of the positive reviews referred to exactly that resistance that the lyrical subject of my poems exhibits. The title of one of those positive reviews “A Woman Again About Struggle and Love” left the strongest impression on me because that is really the essence of what I wrote. There were very few negative reviews, or they never reached me. I remember that someone criticized that the collection remained in that expected power distribution, and some criticized the simplicity of the expression. I actually really like negative reviews, as every negative literary criticism directed at my collection in a certain way was justified. Criticisms are much more interesting to me than praises because, thanks to them, one learns.

As for the non-literary comments, the majority were positive. However, of course, a hundred people – a hundred tempers. I don’t mind if someone doesn’t like what I write. Of course, I consider criticism like “you betrayed Kosovo because you called the song I’m a Serbian woman, but Kosovo is not in my heart, you are” incoherent and I don’t react to it.

My family thought that this hype with the collection would last for two months and that it would all be forgotten quickly, but it was not like that. I am glad that the collection has been living among the public for two years now, and promotions and sales do not stop. People keep giving my poetry to their friends; maybe that is the biggest compliment I could get.

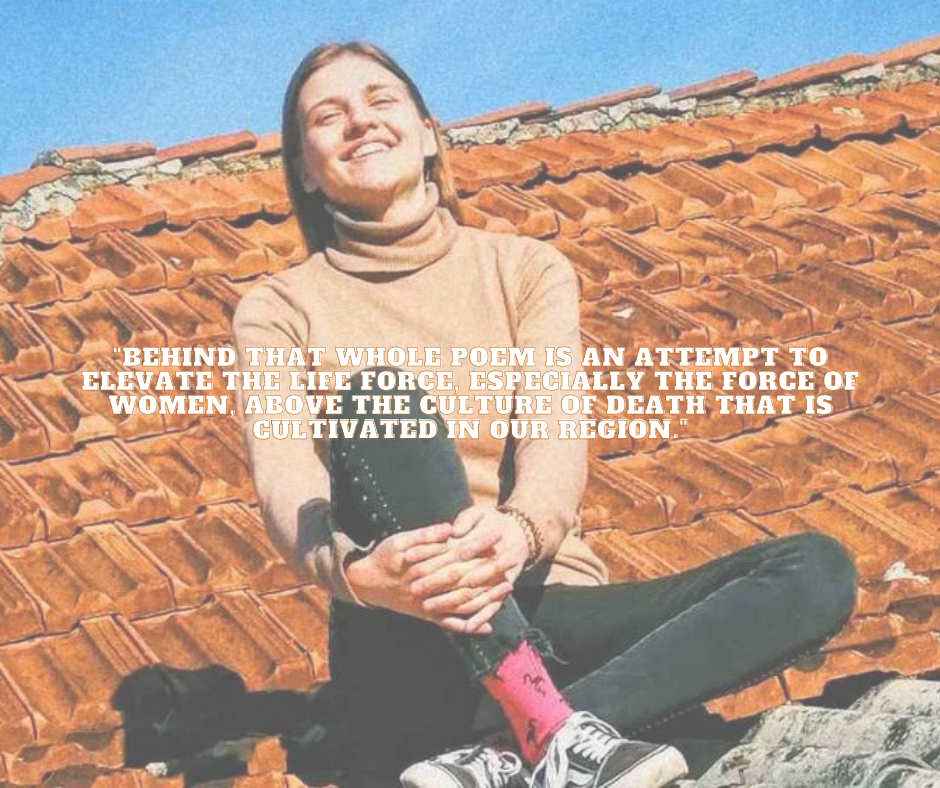

What is hidden behind the line I’m a Serbian woman, but Kosovo is not in my heart, you are?

Behind that whole poem is an attempt to elevate the life force, especially the force of women, above the culture of death that is cultivated in our region. Of course, I say what my intention was, and everyone is free to interpret it as they wish. Literature is always open to the most diverse interpretations, and that is its opulence.

You describe that in your village there are submissive women and dead women. Can you explain it to us a little more? What is the position of women in the countryside in Serbia today?

Where I lived, the position of women was unenviable, and it still is today. From the harsh imposition of traditional gender roles, through violence, to systemic invisibility, and lack of educational opportunities and health care. I am not saying that it is identical everywhere, my lyrical subject is telling her version of the story, what she knows, and what she has witnessed, which is that those women who did not submit did not experience a bright future there.

You don’t have to go to my village or my poetic village to understand the position of women. The current events surrounding the restriction of the right to abortion in the US clearly illustrate our position. The history of civilization is the history of depriving women of their humanity, depriving them of basic rights, such as bodily autonomy. There were women who, after reading my poems, asked me: “Well, is everything like that?” If they had read history critically and from a feminist perspective, they would have understood: yes, everything is like that and it used to be even worse.

How many more Radmilas are there in Serbia who weren’t forgiven for the fact that they are Radmilas (female name)? What does this tell us about girls’ childhoods?

As a child, I used to be angry at the fact that, for example, my dad only wanted to have male children. But now I understand, he knew very well how the women around him lived and he did not want his child to find herself in such circumstances. Therefore, he did not want daughters. But, of course, someone else decides everything and my dad has three daughters – and he is to learn something from that.

The childhood of girls who realize how things are can lead them to not wanting to be girls at all and look for various conscious and unconscious mechanisms to avoid being one. Patriarchy often prevents us from living the whole nature of our femininity, and this is perhaps where the system damages us the most. I think that every woman in Serbia is in some way that Radmila from the collection – some are more and some less able to see that.

You play a lot with the theme of gender roles in your poems. You write about badass girls and metrosexual men. What is your view of gender roles that is behind this?

There is a hidden protest against the demand that the lyrical subject fits into any assigned role, including gender roles.

Among other things, you write lesbian poetry and you managed to bring it to the mainstream. Do you feel alone in this?

If I really succeeded, I would consider it my greatest success. I am not so alone in this in literature, as in the wider non-literary public.

Which women, writers (or those who are not), whether from here or from around the world, are inspiring you?

All women who fight, who are authentic in their work and lifestyle, who are educated, and who always want more are my inspiration. If I start naming them, I will unfairly forget someone. The last thing that inspired me was Nađa Bobičić’s statement during a guest appearance on a show, i.e. a reminder that women in our region were a significant factor in the anti-fascist struggle, and that they defeated even greater fascisms than this that the right threatens us with today. For example, Marija Ratković emphasized the issue of the availability of the HPV vaccine for years and did a lot regarding those initiatives that deal with public health. Dubravka Ugrešić could also be a woman we are proud of.

What helped me a lot was knowing that these and other great women exist, and that, even though I don’t have any women of that caliber in my family, I have this public female line that I can be a continuation of and that has my back.

For those of us who are eagerly awaiting it – when can we expect something new from your pen?

In a year or two.

S.P.