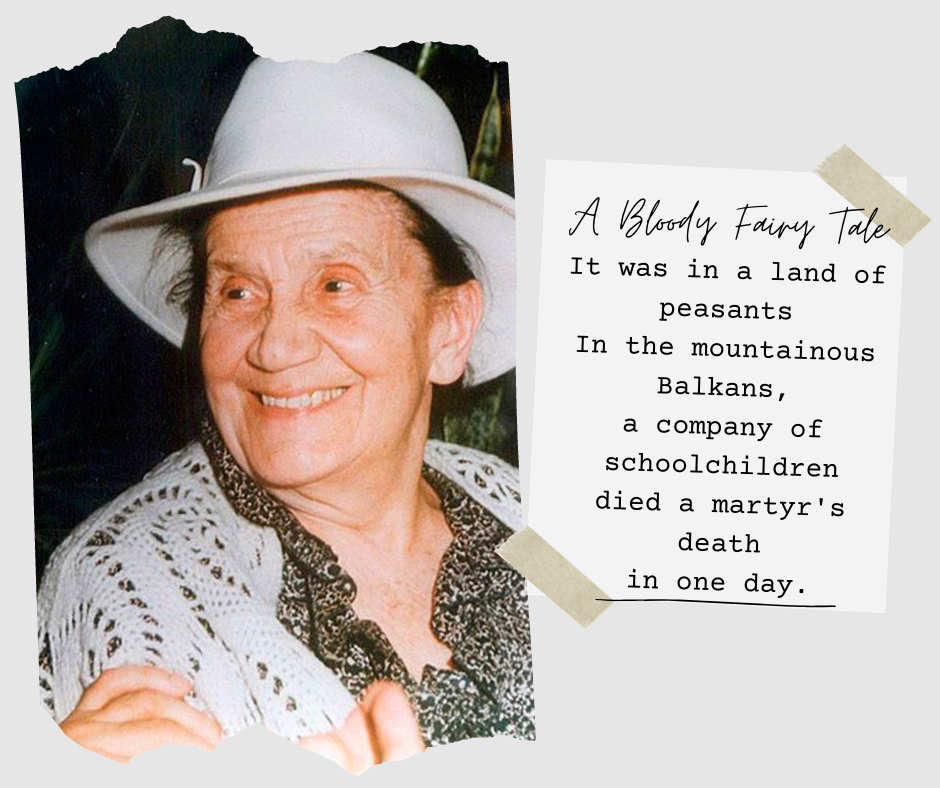

A Bloody Fairy Tale

It was in a land of peasants

In the mountainous Balkans,

a company of schoolchildren

died a martyr’s death

in one day.

Desanka Maksimović was a renowned Serbian poet, writer, and translator. Her life and work left an indelible mark on Serbian literature—she started captivating readers with her poignant and lyrical expression in 1920, when she made a glorious debut in the literary journal Misao. This May 16, we celebrate 125 years since her birth, and in honor of the most beloved Serbian poet of the 20th century, we tackle her most inspiring poem, A Bloody Fairy Tale.

Desanka was a professor at Belgrade’s prestigious First Girls’ Gimnasium. Her teaching career showcased her passion for education and commitment to nurturing young minds, something she would continue to do until her death. The outbreak of World War II halted her career as an educator but could never pause her passion for truth and love. As the German occupation tightened its grip on Yugoslavia, Desanka was soon dismissed from her teaching position and reduced to poverty. She worked odd jobs to survive the war while secretly compiling a collection of patriotic poems.

So many lives were disrupted in the wake of the most gruesome event in history; so many lives ended. Thanks to Desanka, the memories of those who lost their voices too soon will forever live on. The somber verses of A Bloody Fairy Tale, depicting the harrowing Kragujevac massacre, became symbols of the resilience and courage of the Serbian people. The story behind the poem is a perpetual reminder of the two faces of the human coin.

You can find this poem in the collection of Desanka’s poetic gems, Reći ću ti svoju tajnu.

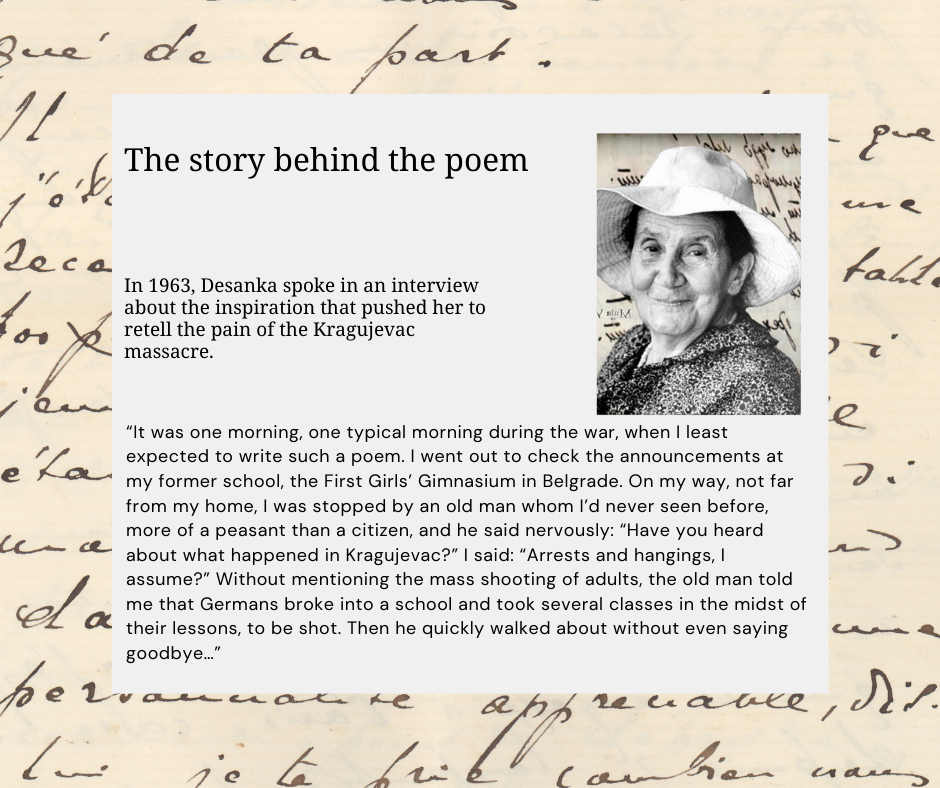

The story behind the poem

Nazi Germany began an invasion of Yugoslavia in April 1941. Yugoslavia was quickly seized and partitioned between the Axis allies. A resistance movement active in the city of Kragujevac and other parts of the country was a thorn in the side of the German occupiers. On October 16, 1941, ten German officers were killed and 26 wounded in an ambush.

The Germans’ response was brutal.

Major Paul König, the highest ranking German officer in Kragujevac, received the order: shoot 100 people for every German soldier dead and take 50 prisoners for every German soldier wounded. The fate of 2,300 people in and around the city was sealed.

High school children, university students, professors, and other civilians paid the price.

A burst of fire echoed throughout the city in the early morning hours of October 21, 1941. The Germans focused on men aged 16 to 60, but that didn’t stop them from taking younger children right out of their classrooms. Two classes of the seventh and eighth grades were taken from the First Boys’ School. Larger students from one class of the fifth grade were chosen to join their peers, as they could pass as older.

The collected men and boys were marched to a field just outside the city called Šumarice on the morning of October 21. That place was chosen because of its advantageous position: it’s a valley with two streams that make it nearly impossible to escape from. Just in case someone did manage to run for it, machine guns were placed on the slopes of the two streams.

Lined up in groups of 50 to 120, the machine guns needed a whole seven hours to hit more than two thousand people.

The gathered men and boys had little time to write notes to their families.

“My dear Rose, forgive me for everything [that happened]

in our last class. Here’s 850 dinars, yours, Boža.”

The principal of the Second Boys’ Gimnasium was leaving for Belgrade on business a few days prior to the massacre. When he noticed something awry was happening in the city—the Germans had started gathering men beforehand and keeping them locked up in sheds—he decided to postpone his trip. He was shot on October 21.

“Me and Aca are leaving together. Father loves you,

live harmoniously.”

One 16-year-old boy was inexplicably taken out of the shooting line and told to go home. One random act of kindness and humanity. A German soldier was executed for refusing to take part in the killings.

“Farewell to you all from Aca. Send regards

to my friend, Danica.”

—Aca, 18

“Go ahead and shoot, I’m teaching my class”

As they faced the firing squad, many people shouted patriotic sayings and sang patriotic songs. The story of one brave teacher echoed throughout the country immediately after the massacre.

Miloje Pavlović was a beloved teacher of the Boys’ Gimnasium in Kragujevac when he was gathered with the rest of his class and taken out in Šumarice on October 21. It is said that he was given a chance to save himself the day before. The famous war criminal and an esteemed member of the paramilitary fascist organization, Marisav Petrović, had recognized Miloje. He said to him: “Look, you’re here too. Do you know, brother, that your life is in my hands now?” According to witnesses who survived the massacre, Miloje responded: “If my life is in your hands, I don’t need it.”

Miloje was accused of raising “generations of communists” in his school, but he had another thing to say to his enemy: “I am not a communist, nor did I teach communism to my students. I am a professor of literature, and I taught them patriotism. I’m not asking you to help me, and I don’t need anything from the likes of you.”

He spent the night in the sheds with his class, and before being mowed down by a burst of machine gunfire, Miloje Pavlović shouted: “Go ahead and shoot, I’m still teaching my class.”

By 2 p.m. that day, Kragujevac had gone silent.

“Have you heard about what happened in Kragujevac?”

In 1963, Desanka spoke in an interview about the inspiration that pushed her to retell the pain of the Kragujevac massacre.

“It was one morning, one typical morning during the war, when I least expected to write such a poem. I went out to check the announcements at my former school, the First Girls’ Gimnasium in Belgrade. On my way, not far from my home, I was stopped by an old man whom I’d never seen before, more of a peasant than a citizen, and he said nervously: “Have you heard about what happened in Kragujevac?” I said: “Arrests and hangings, I assume?” Without mentioning the mass shooting of adults, the old man told me that Germans broke into a school and took several classes in the midst of their lessons, to be shot. Then he quickly walked about without even saying goodbye…”

Whole rows of boys

took each other by the hand

and from their last class

went peacefully to slaughter

as if death was nothing.

“I think it was better for the poem that I was not there that day to witness the tragedy in Kragujevac, that I saw everything only through the eyes of heart and imagination, that I was forced to communicate only the essence, which immediately appeared to me as some kind of a bloody fairy tale: several hundred students born in the same year, perhaps even on the same day, peers even in the exact moments of their deaths… While the stranger was speaking to me, I thought that such a bloody fairy tale could not have happened in England, France, or Italy, that the Germans dared to do it only to our peasants in a Balkan country, which they not only hated but, in their arrogance, despised for being uncivilized peasants.”

The Kragujevac massacre was meant as an act of revenge and a warning. By inflicting brutal punishment on innocent citizens, the German occupiers hoped to inspire fear and destroy any sort of resistance. But they did the exact opposite.

“I often think now how this man is the creator of this poem, which, while he was still speaking, was being born in me. If I had found out about the event through the radio or the newspaper, the poem would certainly have been completely different. It would not have come out in such a melancholic way, like a cry or a tear.”

Either by design or fate, the city of Kragujevac was liberated from the clutches of the Nazis on October 21, 1944.

Truly yours,

Vanja